As the world of cryptocurrencies continues to expand, there has been an increasing number of different decentralised applications offering a range of various activities such as staking, borrowing, lending and NFT trading. Mining as a hobby or as a business has also become increasingly popular due to the potential for passive income.

However, with these activities can come with tax implications that individuals and businesses need to be aware of. In this chapter, we’ll dive into the tax consequences of engaging in these activities in Australia to educate you on the potential tax liabilities.

This course is for educational purposes only and should not be considered tax or financial advice. You should seek out the help of an accountant to obtain advice.

Decentralised Finance (DeFi)

DeFi activities can range from yield farming, staking, providing liquidity to pools, borrowing and lending to earning token rewards. Though it represents financial freedom and innovation, it also introduces intricate tax considerations that are challenging for taxpayers. Navigating through these complexities can be daunting, so we’ve dedicated an entire section to unravelling the many layers of DeFi and tax.

Tax Implications of Staking

Staking refers to the process of holding and validating cryptocurrencies in a wallet to support the operations of a blockchain network. It is somewhat similar to having savings in the bank and earning interest. And just like your savings in the bank, stakers are typically rewarded with additional tokens for their participation (similar to interest).

For individuals staking cryptocurrencies as part of their personal investment strategy, the rewards received from staking may be considered ordinary income subject to income tax. The fair market value of the tokens received at the time of receipt is included in the individual’s assessable income.

Keep in mind, if the individual then disposes of their staking rewards later on in the future (either in exchange for another cryptocurrency or for fiat currency), they will also be subject to capital gains tax with the market value of the rewards at the time they were received forming the cost basis for the capital gains or loss.

Fictitious Example

Income Tax

- Let’s say someone holds 200 SOL in a Solana staking pool.

- After a given period, they receive 25 SOL in staking rewards with a market value of $500.

- This $500 worth of SOL is considered income and will be added to their total assessable income.

Capital Gains Tax

- Continuing, say they then decide to sell your SOL at a future date

- They may be subject to Capital Gains Tax (in addition to the income tax they’ve already incurred), with the cost base now being $500 (the market value of the staking rewards when they received them).

- For example, say they held onto that 25 SOL, and it increased to a value of $1200, at which time they decide to sell.

- Cost base: $500

- Capital proceeds: $1200

- Capital Gains = Proceeds – Cost Base = $1200 – $500 = $700

As seen in this scenario, this fictitious person has incurred BOTH income and capital gains taxes.

Tax Implications of Yield Farming

Yield farming, a DeFi strategy where people can earn token incentives by providing assets to a protocol, also has tax implications. Like staking, earning new coins or tokens may generally be considered income, attracting Income Tax based on their fair market value at the time of receipt.

However, an increase in the value of tokens through yield farming may be subject to Capital Gains Tax (CGT) upon disposal. Please note the ATO has yet to provide explicit guidelines on yield farming, making consultation with a crypto-informed tax professional highly advisable.

Tax Implications of Liquidity Pools

As a liquidity provider in DeFi, people add tokens to a pool and receive liquidity tokens in return. If they earn new coins or tokens, they may qualify as income depending on how they are distributed and therefore be subject to Income Tax. If these liquidity tokens appreciate, this increase may fall under the CGT regime upon disposal.

Adding or removing liquidity from the pool, involving the receipt or disposal of a token may also trigger a CGT event depending on the individual situation. As the ATO has yet to finalise specific DeFi and liquidity pooling rules, consulting with a crypto-savvy tax professional is recommended for accurate reporting and compliance.

Tax Implications of Borrowing and Lending

Borrowing against crypto holdings in DeFi is generally not considered a taxable event unless the collateral is liquidated. Suppose the collateral, which is typically in the form of a cryptocurrency, is sold or exchanged as part of a liquidation of the loan. In that case, this transaction is likely to constitute a disposal, triggering a CGT event based on the increase in the asset’s value at the time it was acquired.

On the other hand, people that lend cryptocurrencies in DeFi and earn interest may need to treat this interest as income for tax purposes. Therefore, it should be reported as such and will be subject to Income Tax. The amount of income is typically determined based on the fair market value of the interest received at the time it is earned.

Despite the likelihood of these treatments, it’s important to note that the ATO has yet to provide official rules on borrowing and lending within DeFi. Thus, seeking advice from a tax professional familiar with cryptocurrencies is essential to ensure accurate reporting and compliance with all relevant Australian tax laws.

Tax Implications of Airdrops

Airdrops involve the distribution of free tokens to cryptocurrency holders as a promotional or reward mechanism. For example, some early adopters of Arbitrum were rewarded with a generous airdrop earlier this year.

In most cases, airdrops are taxed at the tokens’ fair market value at the time of receipt and are therefore included in their assessable income for income tax purposes. And just like staking rewards, if you dispose of your airdropped tokens at a later date, you will be subject to capital gains tax with the market value of the airdrop at the time it was received, forming the cost basis for the capital gains or loss.

However, if the airdrop is an initial allocation of tokens and the tokens were never previously traded, and thus, do not have a fair market value, they may not be treated as income. Instead, they may be assigned a cost basis of $0, meaning that if a recipient ever disposes of them, the full proceeds will be subject to CGT.

Interesting Fact

The first airdrop ever in crypto history happened in March 2014 when Iceland launched Auroracoin.

Tax Implications of Mining

Mining involves validating and adding new transactions to a blockchain network. Miners are rewarded with newly minted cryptocurrencies along with transaction fees. The tax treatment of mining depends on whether it is conducted as a personal or business activity.

Now you might be wondering whether a miner is seen as an individual or a business that is mining cryptocurrency. The main difference between the two tends to be that someone who’s mining as an individual is doing it as a hobby and may have a small setup at home. However, someone who’s mining crypto as a business tends to have extensive equipment set up and is expecting to generate a decent amount of income.

Mining as an Individual

For individuals mining cryptocurrencies as a personal investment or hobby, the proceeds generated are generally not subject to income tax. Instead, they will be liable for capital gains tax only when they choose to dispose of the mined coins.

Remember, since the coins were obtained through mining, the cost basis is considered $0; therefore, the entire amount then received when selling mined coins represents the capital gain.

Mining as a Business

If mining is conducted as a business activity, the income generated is often treated as assessable income and is, therefore, subject to income tax. The business would also be subject to capital gains tax when they dispose of the mined coins in exchange for another cryptocurrency or fiat currency. However, the benefit for those mining as a business is that expenses incurred in running the mining operation, such as electricity costs and mining equipment, may be tax deductible (which is not the case for those mining as individuals).

Did You Know?

One of the largest NFT sales by an artist was “Everydays: The First 5000 Days” by Beeple (Mike Winkelmann). This digital artwork, consisting of a collage of 5,000 individual images created over 13 years, was sold as an NFT for a staggering $69.3 million in March 2021. This sale marked a significant milestone in the NFT space, attracting global attention and setting a record for the highest-priced NFT artwork sold to date.

Tax Implications of Forks

Forks occur when a blockchain network undergoes a significant change, sometimes resulting in the creation of a new cryptocurrency. There are two types of forks: soft and hard forks.

Hard Forks

In the case of a hard fork where a new cryptocurrency is created, the individual receives an allocation of the new cryptocurrency based on their holdings of the original cryptocurrency.

The new cryptocurrency received is considered ordinary income and subject to income tax at its fair market value at the time of receipt. And similar to staking rewards & airdrops, the cost base of the new cryptocurrency is also set at the fair market value at the time of receipt for future CGT calculations.

Soft Forks

There are no immediate tax consequences for soft forks where no new cryptocurrency is created. The individual’s original cryptocurrency holdings remain unchanged, and no income or CGT event is triggered.

How are NFTs taxed?

You may or may not be familiar with NFTs (feel free to check the Swyftx course on NFTs here). Still, as a refresher, NFTs are unique digital assets that represent ownership or proof of authenticity of a particular item, such as digital artwork, collectibles, or in-game items. Regarding taxation, the ATO treats NFTs similarly to other forms of cryptocurrencies.

For individuals who acquire and hold NFTs as an investment (as opposed to personal use), any capital gains made upon selling or disposing of an NFT may be subject to CGT. The CGT event occurs when the NFT is sold or exchanged for another cryptocurrency or fiat currency. Capital gain is calculated by subtracting the cost base (purchase price) from the selling price (proceeds).

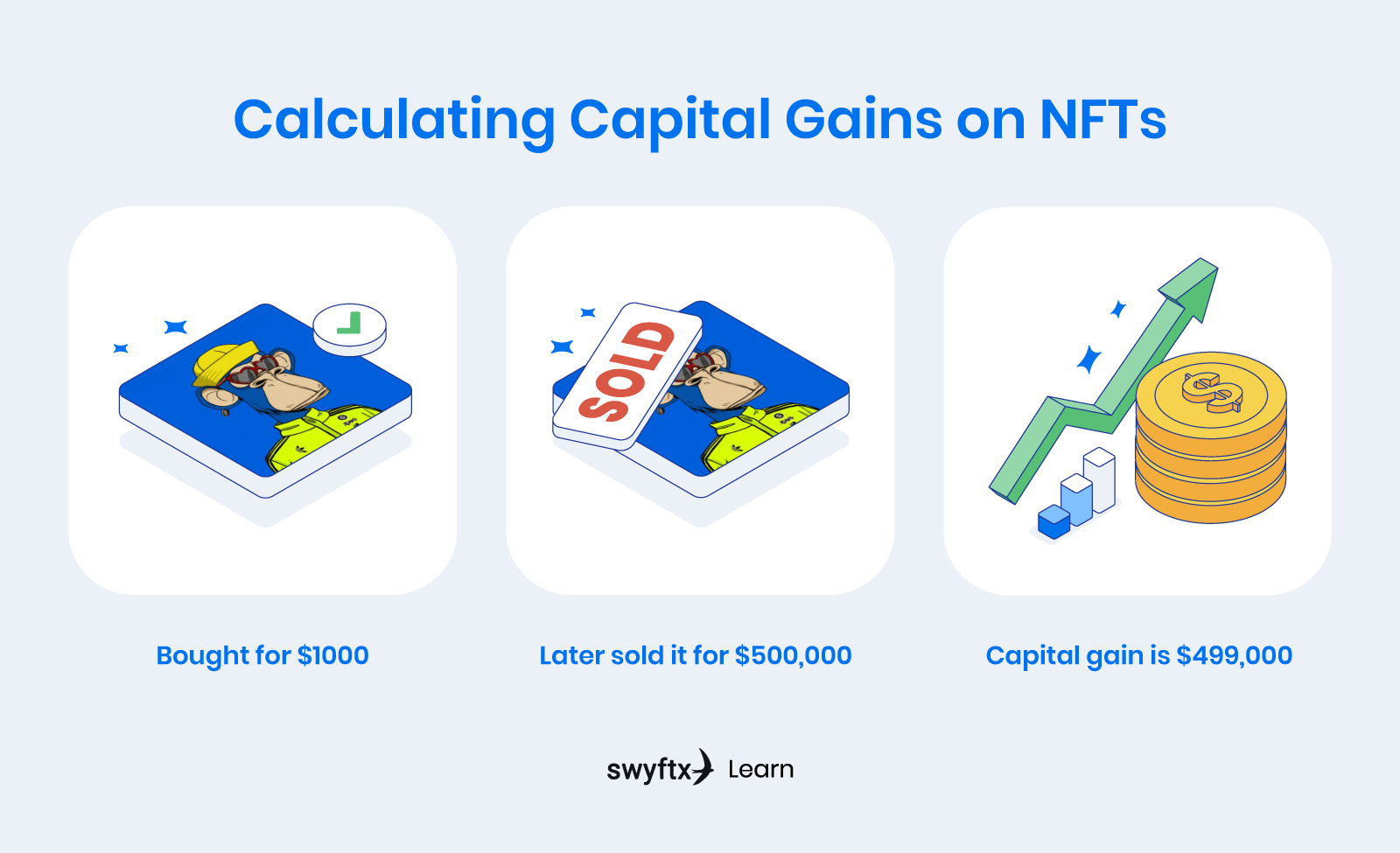

Example

- Suppose you purchased a Bored Ape NFT for $1,000 (bargain!)

- You then later sold it for $500,000.

- The capital gain is calculated by subtracting the cost base from the selling price.

- In this fictitious example, the capital gain would be $500,000 – $1,000 = $499,000.

What if you’re selling NFTs for a living?

For those who create and sell NFTs as part of their business (e.g., artists who sell their own digital artwork as NFTs), the income generated is generally treated as business income and, therefore would be taxed as part of business earnings.

Authored by Crypto Tax Calculator

Australian-made to ATO standards, CryptoTaxCalculator (CTC) simplifies crypto taxes for Aussie investors. Whether you’re simply buying and holding, staking or diving into DeFi and NFTs, CTC has you covered.

Simply connect your accounts, follow the automated tax-saving suggestions and generate your ATO-ready report. Claim 20% off new CTC plans using code SWYFTXTAX. See you soon!

Next lesson

Disclaimer: The information on Swyftx Learn is for general educational purposes only and should not be taken as investment advice, personal recommendation, or an offer of, or solicitation to, buy or sell any assets. It has been prepared without regard to any particular investment objectives or financial situation and does not purport to cover any legal or regulatory requirements. Customers are encouraged to do their own independent research and seek professional advice. Swyftx makes no representation and assumes no liability as to the accuracy or completeness of the content. Any references to past performance are not, and should not be taken as a reliable indicator of future results. Make sure you understand the risks involved in trading before committing any capital. Never risk more than you are prepared to lose. Consider our Terms of Use and Risk Disclosure Statement for more details.

Article read

Article read